Architecture is more than a physical structure; it is a powerful force that influences how we feel, behave, and interact with our surroundings. While we frequently focus on the aesthetics and structural brilliance of buildings, we often miss how interiors have a significant impact on our psychology and wellbeing.

Architecture and Emotion: The Invisible Dialogue

Walking into a cathedral may fill you with awe. When you enter a cramped, poorly lighted hallway, you may feel apprehensive or uneasy. These emotional responses are not arbitrary; they are profoundly ingrained in how our brains see space. The scale, dimensions, lighting, colors, textures, and acoustics of a location can elicit certain emotional and physiological responses.

For instance:

-

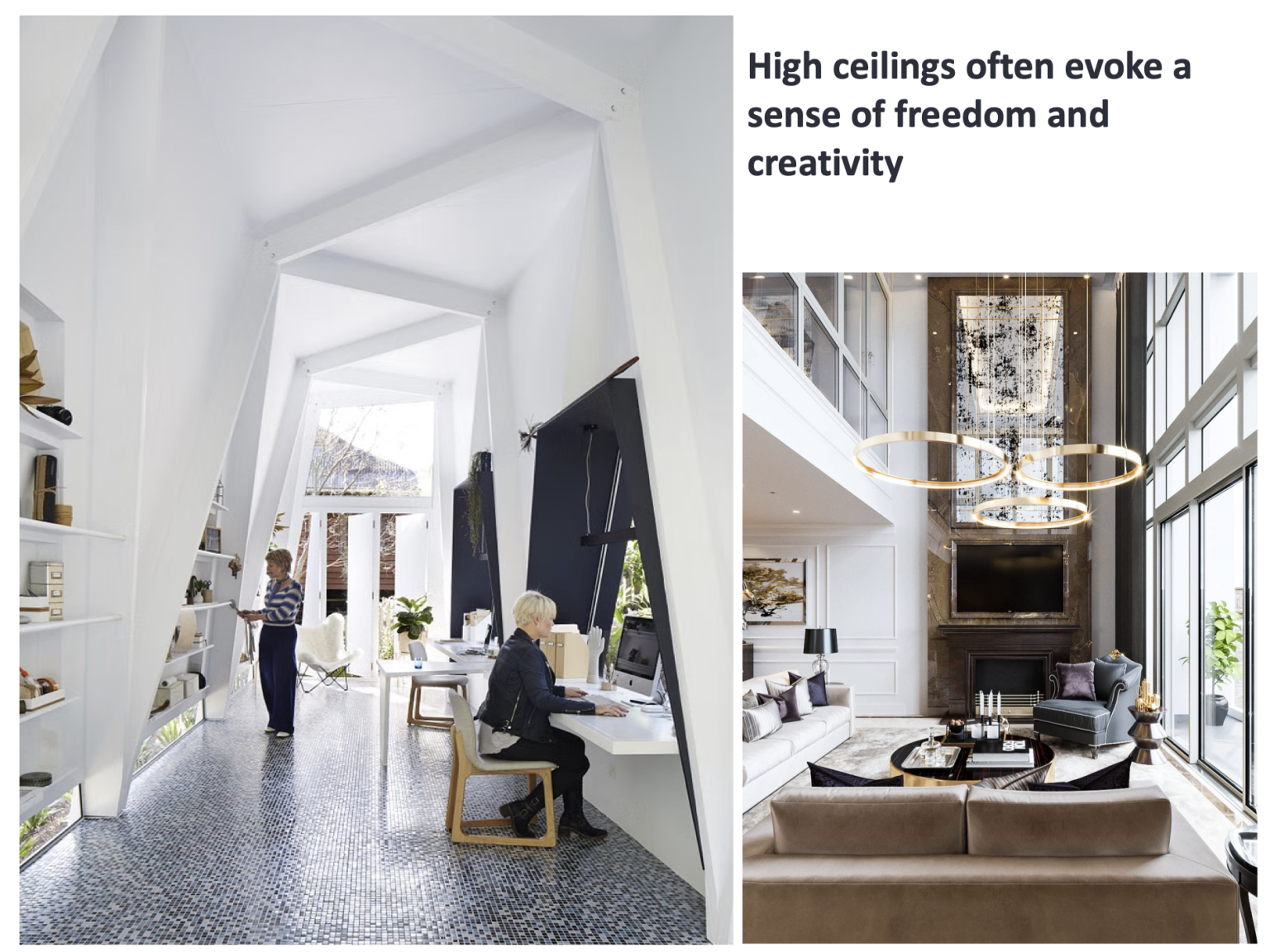

- High ceilings often evoke a sense of freedom and creativity.

-

- Warm lighting fosters calm and intimacy.

-

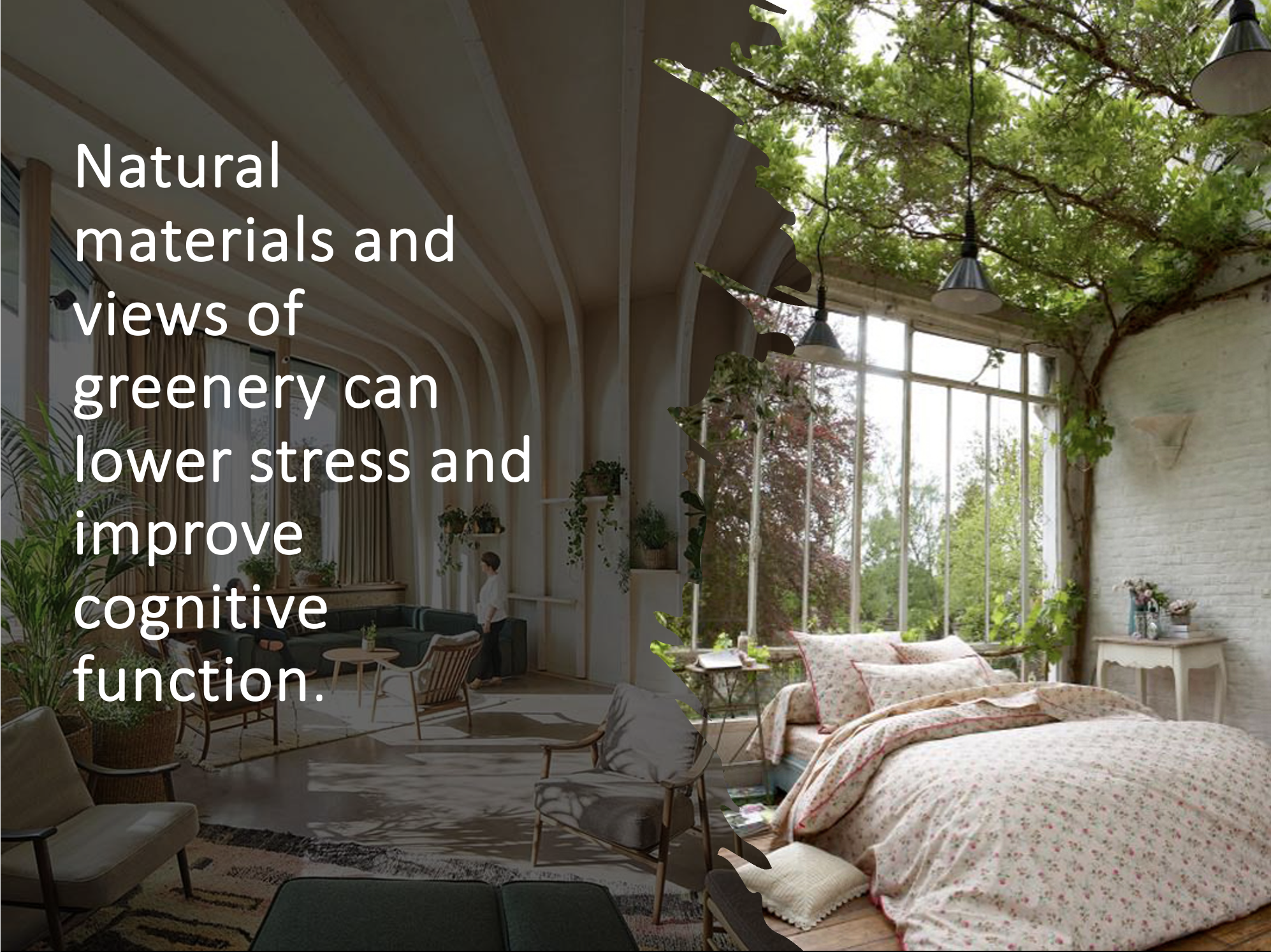

- Natural materials and views of greenery can lower stress and improve cognitive function.

Designing for Behavior

Urban planners and architects consciously (or unconsciously) influence behavior through design. Consider how the design of a public plaza stimulates meeting and conversation, or how hospital rooms with windows that overlook nature can speed up rehabilitation.

Some real-world examples:

-

- Open office layouts were intended to promote collaboration, but often result in reduced concentration and privacy.

-

- School environments with vibrant colors and flexible seating can enhance student engagement.

-

- Transit hubs with clear visual lines and wayfinding reduce confusion and improve flow.

Crowding vs. Community

Density is not automatically negative. Smart spatial planning in congested regions can promote community and engagement. The idea is to instill a sense of territorial control and access to personal and communal locations. For example, creating neighborhoods with semi-private courtyards or stoops promotes casual social interaction while respecting personal boundaries.

Cognitive Mapping: Navigating with Ease

Good architecture allows people to navigate intuitively. This notion, known as cognitive mapping, describes how quickly people perceive and mentally map an area. Spaces that are overly homogeneous, inadequately lighted, or lack unique identifiers can cause disorientation. On the other side, landmarks, color labeling, and logical pathways provide comfort through clarity.

Conclusion: Human-Centric Architecture is the Future

As we advance towards smarter and more inclusive design, the interaction of psychology and architecture becomes increasingly important. Spaces should serve more than just a functional purpose; they should heal, inspire, and empower.

Architects and planners must ask not only “What will this look like?” but also “How will this make people feel?”